I’m sure that most of us have spent time looking at monuments in a graveyard or church at one time or another. On holidays or at a funeral, reading the inscriptions on headstones, we may secretly (when at a funeral) or loudly (when on holidays) try to spot the oldest or youngest deceased or simply the oldest grave in the plot.

Living in Ireland, one is spoilt for choice when it comes to visiting old and fascinating burial places, ranging from the ancient passage tombs such as Newgrange in county Meath, to Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin with the final resting places of many Irish heroes. Both are in fact tourist attractions, complete with guided tours.

It comes as a shock to my Irish friends when I tell them that a final resting place in my native Holland may not be all that final after all. I would have a hard time trying to find the graves of some of my relatives, for example, even if I know where they were buried. This is because cemeteries in Holland’s urban areas have long run out of space. Just as most Dutch people rent their home during their lifetime, their final resting place is also — rented.

Around the city of Rotterdam, the average rental period for a grave is 25 years. I imagine that means that if you’re in your seventies and decide to pick that nice spot under the big tree, you’d better keep in mind that if you live for another 10 or maybe even 20 years, you’ll have precious little time left in your “final” resting place. When the rental period ends, surviving relatives are notified and asked if they wish to renew the lease — it seems that in most cases, they let it go.

If you had planned to spend your sunset days in Holland and this has turned you off, then you’ll be glad to know that you can always buy a grave, in which case your mortal coil does get the eternal rest you had in mind. Also, most cemeteries in rural parts of the Netherlands do not have the same space problems as their urban counterparts.

One wonders what happens to those graves that are cleared when their lease is up. Of course the official guidelines tell us about the sensitivity surrounding exhumation, and how the remains are placed in smaller boxes and interred in a communal vault — the practise will vary between cemeteries. It appears that these practises have not always been so sensitive, however.

When I spent a weekend with one of my friends in secondary school, he took me to the grounds of a church in a nearby village. At the time, we were going through a teenage Gothic Horror phase, reading Edgar Allan Poe and the like. The church grounds were of interest because part of the old graveyard had recently been cleared, and the freshly dug soil had been distributed around the walls of the church, presumably to provide bedding for plants. To my amazement, the white bits that could be seen scattered among the lumps of soil turned out to be — bones. Teeth, vertebrae, bits of ribs and skull… they were definitely human. Weirdos that we were, a few samples ended up in our pockets.

Of course the force of nature will sometimes compromise a final resting place, even in Ireland — where the thought of renting a grave is almost as abhorrent as renting one’s home. The torrential rain of last October washed away part of the graveyard at St. Mary’s Abbey in Howth, exposing some of the coffins. Pictures that appeared via Twitter and Facebook have since been removed from the more established news sites, probably because it emerged that the affected graves were quite recent.

Mud slides and rental graves notwithstanding, most burial places are of a more permanent nature, thankfully. My morbid teenage fascination with such places appears to have stayed with me, and over the years I have roamed among the permanent addresses of the faithful and not-so-faithful departed in various locations.

Père Lachaise in Paris was one of my first encounters with a different approach to honouring the dead than what I was used to. This incredible necropolis is home to the remains of countless famous people, Edith Piaf, Jim Morrison, Victor Hugo and Chopin among them. Recently the cemetery featured on the Irish news when the tomb of Oscar Wilde was restored, having become the victim of thousands of kisses.

A completely different experience awaited me when I visited the Piskariovskoye Memorial Cemetery in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg — once again). Around half a million victims of the Nazi siege of the city lay buried in enormous mass graves, marked only with a stone with the year on it. Tschaykovsky’s “Pathétique” sounded from dozens of speakers around the cemetery, adding to the gloom.

Much more colourful was the town cemetery in Comares in Andalusia, Spain. Perched on top of a massive rock, the location does not lend itself to the traditional method of placing the deceased six foot under. Instead, they are stacked up to more than six foot above the ground in drawer-like tombs, with neighbours on all sides. One gets the feeling of navigating the cemetery like supermarket aisles.

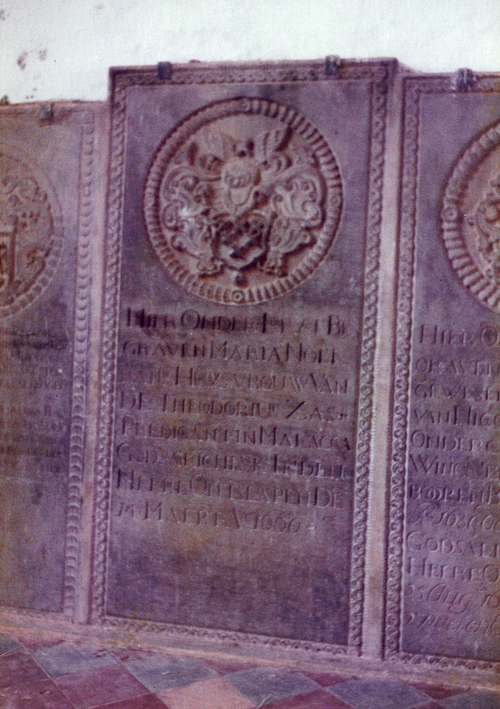

Apart from the quirky architecture, the historic ties between Holland and Malakka in Malaysia become apparent when visiting the ancient graveyard beside St. Paul’s Church in the centre of the old town. Dozens of weathered headstones bear testimony to the adventurous souls who sought to start a new life in a new world, at a time when such an undertaking was far more dramatic — and permanent — than we can imagine. Dating back to the 17th century, the most elaborate and best preserved monuments adorn the graves of merchants and their families, whereas ordinary citizens have to make do with more clumsily carved markers of lesser quality. Plus ça change.

Back in Ireland, one of the more bizarre burial spots can be found near the village of Glencree in the Wicklow Mountains, south of Dublin. Nestled in the shade of a steep rock we find the picturesque German War Cemetery. That’s strange, because the last time we checked our history books there was no mention of a war involving German troops on Irish soil. It turns out that most graves are from the time of “the Emergency”, among them those of Luftwaffe personnel on one of their raids who somehow managed to miss England (where they refer to this era as World War II). The plot thickens when we spot a grave from 1947, when even outside Ireland the War was over. This grave belongs to Dr. Hermann Görtz, a German spy based in Ireland who committed suicide when the Allies were hot on his trail. De mortuis non est disputandum, or something like that.

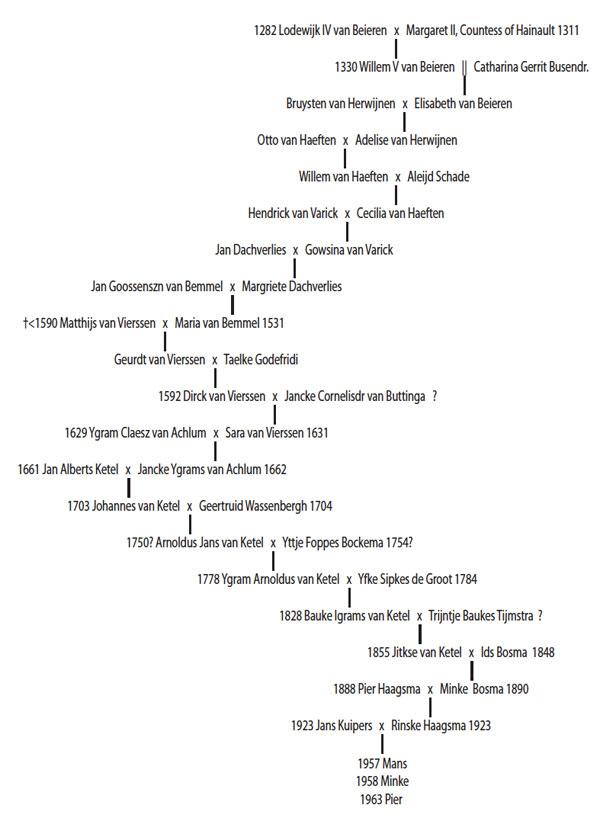

I’ll finish by referring back to my first blog post. My uncle Ids Haagsma was executed by the Nazis in November 1944; his body was found after the war, in a mass grave on the Waalsdorpervlakte near the Hague. He was re-interred, with full military honours, at the Zuiderbegraafplaats in Rotterdam, and later at the Ereveld (Field of Honour) in Loenen — the final resting place of some 4,000 casualties of various wars.

May they rest in peace.