Rummaging through a pile of old newspapers, kindly left behind in the attic by our home’s previous owners, I came across this little gem in the Evening Press of Friday, 10th March 1972. In the light of my well known interest in all things Napoleonic, I see it as my duty to re-publish the article here in full for you all to enjoy, 47 years after it first (and until now, last?) appeared.

A funeral fit for the Duke

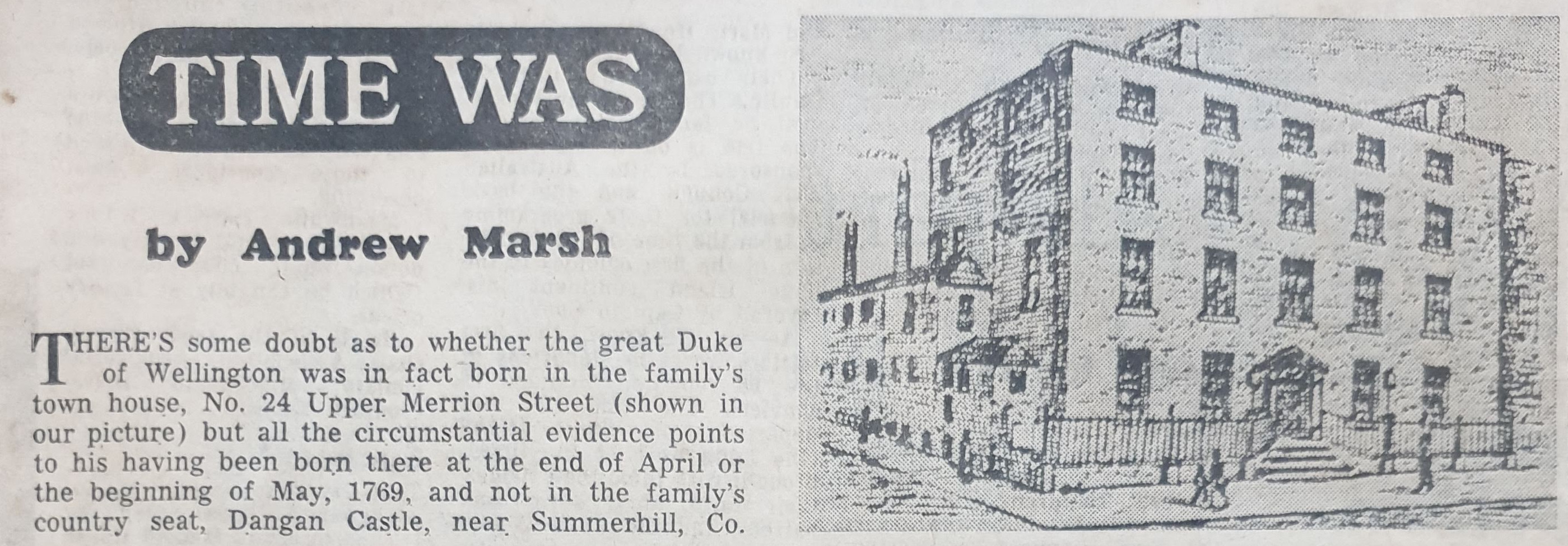

by Andrew MarshTHERE’S some doubt as to whether the great Duke of Wellington was in fact born in the family’s town house, No. 24 Upper Merrion Street (shown in our picture) but all the circumstantial evidence points to his having been born there at the end of April or the beginning of May, 1769, and not in the family’s country seat, Dangan Castle, near Summerhill, Co. Meath.

But there’s no doubt as to where he died. Early in the morning of September 14 1852, when he was staying at one of his official residences, Walmer Castle, on the Kent coast, he suddenly called for his valet, murmured ‘Send for the apothecary,’ and expired. He had suffered a severe stroke. He was aged eighty-three. England was thrown into a flap. Wellington seemed always to have been there and as if he always would be there. He was a national institution and respectable folk are always upset and indeed somewhat indignant when a national institution vanishes suddenly. Their sense of stability and security is threatened.

Wellington in his later years was Britain’s supreme national institution. Things had got to the stage when the Government couldn’t buy a new mop for House of Commons charwoman without consulting ‘The Dook’. When the enormous glasshouse known as the Crystal Palace was built for the 1851 exhibition, the pet project of Victoria and her Albert, the place became infested with sparrows. The little birds were no respecter of persons below and couldn’t be shot for fear of damaging the glass. Victoria consulted The Dook. ‘Try sparrowhawks’, he growled, and Victoria was so overwhelmed by the simplicity of the solution that she hadn’t the presence of mind to ask him how the sparrowhawks were to be got rid of after they had got rid of the sparrows.

Naturally so remarkable a man had to be given a Sate funeral, and Victoria and her Albert decreed that it must be the funeral to end all funerals. Albert took a hand in designing the funeral carriage. It turned out to be the size of a combine harvester, was made of cast iron, and was embellished with military trophies of truly Victorian splendour.

Had The Dook been there to comment upon the carriage he would have acidly pointed out that it was so heavy it would be bound to sink in the first bit of soft road surface encountered. Which is exactly what it did. Officials also discovered at the dress rehearsal that it was too wide to go through the special ceremonial arches that had been erected.

Many days elapsed between The Dook’s death and his burial in the crypt of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, so England had time to pull itself together and to remember that it was the nation of shopkeepers.

Accordingly vintners began advertising ‘The Duke of Wellington’s Funeral Wine’ while bakers produced ‘The Duke of Wellington’s Funeral Cake’ and the tailors, with astonishing lack of humour, announced a ‘Funeral Life Preserver’. The happy owners of houses along the funeral route offered front row accomodation on first floors ‘with use of piano.’ The prices were steep.

‘THE DUKES’S FUNERAL – To be Let a shop window with seats erected for about 30, for 25 guineas. Also a Furnished First Floor with two large windows. One of the best views in the whole range from Temple Bar to St. Paul’s: price 35 guineas. A few single seats one guinea each.’

A reminder that England is also the land of the hypocrite was provided by a pious Fleet Street householder who offered four front seats at £1 each to clergymen ‘upon condition that they appear in their surplises.’ The householder’s other seats were 40s., 30s., 15s. and 10s.

The there was the widowed lady who offered for sale ‘a Lock of Hair of the late Duke of Wellington… cut of the morning the Queen was crowned.’ Someone else offered ‘a waistcoat in good preservation, worn by his Grace some years back, which can be well authenticated as such.’

But the gem of the collection was a copy of ‘The Death of Napoleon’ alleged to have been torn up by the Duke and thrown by him from the carriage windows as he was riding through Kent. The pieces of the book were collected and put together by a person who saw the Duke tear it and throw the same away. It was offered to the highest bidder of over £35.Evening Press,

10 March 1972

Andrew Marsh was a pseudonym of John O’Donovan (1921 – 1985), a Dublin playwright who wrote a weekly column about Ireland’s past entitled “Time Was” in the Evening Press during the 1960s and 1970s.