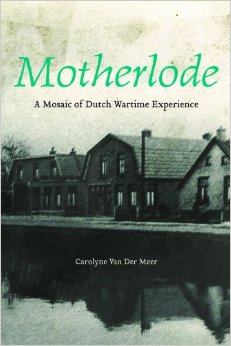

The 8th November marks the anniversary of my uncle’s arrest by the Nazis in 1944. I wrote this story featuring the event earlier this year.

Of course I know who you are. You’re the youngest of the family that lived here the longest. People come and go, especially in this part of town. Everyone here rents their home, as they’ve been doing since these houses were built, about a hundred years ago. The people that live here now only moved in recently, you wouldn’t know them. But your family somehow managed to pass on this home from one generation to another.

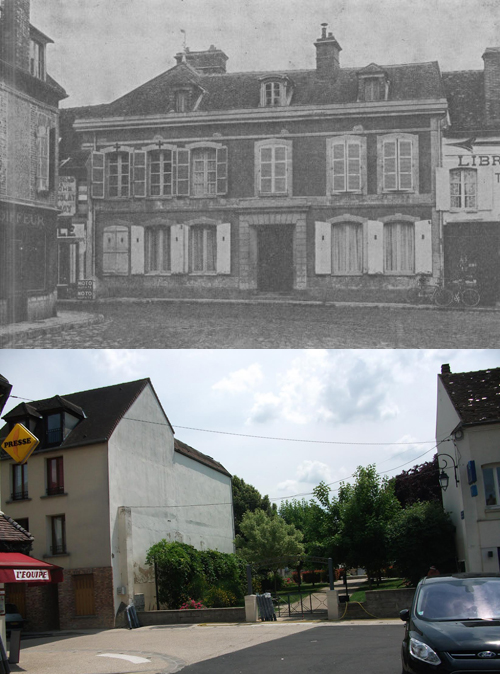

This is a nice part of town, or at least it used to be. It was even a bit famous for its forward thinking at the time. Some city planners in the early 1900s felt that working class people should live in proper homes, with running water and little gardens front and back, imagine that. When you moved in here you were only a little boy and everything must have seemed a lot bigger then, even these little gardens. As it happened, you were already familiar with the place, because your grandparents lived here, and your mother had grown up under this very same roof. Well, not quite the same roof, because it had more chimneys then, because of the coal fires.

This is a nice part of town, or at least it used to be. It was even a bit famous for its forward thinking at the time. Some city planners in the early 1900s felt that working class people should live in proper homes, with running water and little gardens front and back, imagine that. When you moved in here you were only a little boy and everything must have seemed a lot bigger then, even these little gardens. As it happened, you were already familiar with the place, because your grandparents lived here, and your mother had grown up under this very same roof. Well, not quite the same roof, because it had more chimneys then, because of the coal fires.

But why are you here, anyway? Not to visit your family, that’s for sure. You’ve all moved on and your family were never really from this city to begin with. Your grandparents were one of the first to arrive here, that must have been in the early thirties. I guess it was a bit tight, four bedrooms for two adults and six children. But they came from a rented three bedroomed terraced home from another part of town. So they managed to trade up, without the trading.

Maybe you’re trying to remember this place as it was when you were a child, when you came to visit your grandparents. It was magic, you’ll have to admit that. There were nooks and crannies and secret rooms and doors and strange cabinets, wooden floors with dark red rugs and rough hessian carpets that would hurt your knees when you crawled under your grandfather’s rolltop desk. In wintertime, the only place that was warm was the living room, thanks to the big shiny black stove. In the rest of the house you had to make do with electric bar heaters that always smelled of burning hair. And at night time in bed you’d have a metal hot water bottle, with a wool cover handknitted by your grandmother, so you wouldn’t burn yourself.

There were trees and shrubs and hedgerows everywhere, it didn’t seem like you were in the city at all. And not only were the houses made of redbrick and matching red roof tiles, even the streets themselves were paved with the same red bricks. There was a tram that ran through this very street, they replaced that with a bus route in the early seventies. That was a disaster for the brick paving, the buses were too heavy and ploughed furrows beside the curbs at the bus stop. Yes, the stop is still here, right at the front door. The furniture would shake and the windows rattle every time a bus came by, but you never noticed, because you were so used to it.

But I have seen more than just buses and trams going by these windows. The greengrocer and the milkman passed by here on their rounds, with horse and cart. The neighbourhood policeman on his bicycle. Wedding cars parked right in front, on the occasions of happy couples tying the knot, including your own parents. An ambulance pulled up to take your grandmother to the nursing home, and later your grandfather, and at one stage your mother, when she had appendicitis and you were afraid that she would die, as the paramedics struggled to get her down the narrow stairs on a stretcher. Cars with prams folded in the boot and baby seats in the back, cars with bicycle racks on top, cars with tow bars and caravans, I’ve seen them all come and go over the years. There’s been hearses too, but that’s to be expected when you’ve been around as long as I have. And of course the moving vans, in all sorts and sizes. The big truck when you moved in with your family. The van belonging to a family friend when you moved away from home to study and explore the world.

And one day, when your mother was still a girl, the armoured cars arrived, and the motorbikes with sidecars, and marching soldiers with their boots pounding the redbrick roads. Dozens of dark propellor planes droned overhead. Your grandmother shook your mother awake that morning, “Wake up! It’s war!” Your grandfather was not going to let these brutes take over his town without taking firm action. Jumping on the brand new bicycle he’d won at a raffle a few days earlier, he set off towards the river. Less than ten minutes later he was back at the front door, on foot, his bicycle unceremoniously confiscated by an enemy paratrooper at the bottom of the street.

Your grandfather was well known and respected in the local community – after all, he had made sure the garden village got its own church, which was built before the war and where he laid the foundation stone. You should go and have a look, that stone with his name engraved on it is still there, hidden behind some bushes.

Life continued as the war rumbled on. Your mother moved away to work as a nanny, your uncle Jacob got married, and then your aunt Jitske. Ids, the second oldest in your mother’s family, got a job at the greengrocer’s and I watched him go by on his rounds with the horse and cart.

Ids was your mother’s favourite brother, not two years older than she was and full of life and mischief. Always in the thick of things, messing with his brothers, annoying your grandmother. A hard worker, with a heart of gold. Through the youth club at the church – yes, the same church your grandfather helped to build – he got to know other young people who were just as upset by the occupation as he was. The grocer’s cart became a mobile meeting point for members of the underground movement. He was deemed too young to take part in armed resistance, but he helped with the distribution of illegal newspapers. Almost every day, under cover of carrots and potatoes, he provided real news to likeminded people in the area.

That night, when there was a knock on the front door, he was sure it was his friend Peter, coming over to listen to the radio. “Calm down, I’m coming, I’m coming,” he shouted down the stairs as there was another loud knock. He was standing on the landing with the radio in his arms, when your grandfather opened the door. “Now we’ve got you,” said the uniformed stranger as he pushed past him and headed straight up the stairs. Three more soldiers burst in after him, loud and large and violent and angry.

Of course they knew who he was. He had been betrayed by one of his own, the grocery cart had sprung a leak. They dragged him and your grandfather off to the local police station, your grandmother sick with worry. Your grandfather came back here after a few hours. He last saw Ids in the corridors at the police station. “Dad, I take responsibility for everything”, he heard Ids say as soldiers pushed your grandfather out the door.

Your mother didn’t know any of this. She was living in a part of the country that had been liberated a few weeks earlier and contact across enemy lines was impossible. It wasn’t until the end of the war, six months later, that she learned the news from a letter your grandparents managed to get to her. They had lived through a horrific winter of fear and hunger. Every day, your grandfather had searched the city, looking for his son. Making enquiries with the occupiers. Looking among the civilian victims of yet another reprisal execution. And when the war was over, he placed ads in the personal columns in local and national newspapers. Has anybody seen my Ids?

His body was found a year later. He had been shot the day after he was arrested and was buried in a mass grave. He was twenty-three.

A few decades later you came to live here yourself, with your mother and your brother and sister. Your father had died, and your grandfather was living here all by himself, after your grandmother had had to move to a nursing home. Your mother had come back home, but for the three of you this was an entirely new beginning.

You each had your own bedroom – not like your mother when she was young, who shared with your aunt Jitske. And two of your uncles were in that one bedroom that became your grandfather’s study later, hard to believe. Your uncle Ids and uncle Jacob shared the bedroom at the back of the house – the one that later became your room – until Jacob got married. It had a bar heater set in the corner, it was still there when you moved in. Remember that time you decided to redecorate that room? You started stripping the wallpaper off the walls down to the plasterwork, and to your surprise your handiwork revealed large black letters. “Ora et Labora” was written in impressive Fraktur script across the full width of the wall – “Pray and Work”. Your mother was amazed. She told you it had been painted by Ids, before the war, and although it sounds like a humourless motivational slogan, it was simply the name of that youth club at the church where he went every weekend.

It’s my duty to provide shelter and security, and that November night at the end of the war, I failed. Your family didn’t hold it against me, though. The ugly scar above the bedroom door, where a soldier jammed his bayonet looking for a secret hiding place, was still there when you were doing your decorating. Your mother would often point it out, as a memorial to the past. It’s now long gone and long forgotten. The house was renovated in the eighties and everything is much roomier, lighter, brighter. There’s a proper kitchen now, and a proper bathroom with a shower. But some small signs from the past are still there, although I’m probably the only one who knows where to find them.

You’ve stood there long enough, looking at me. Go on, ring the bell and ask if you can take a look at the wall outside the back door. If you look closely, you’ll see that some of the bricks along the edge of the doorpost are strangely smooth. That’s because your grandmother used to sharpen her kitchen knives there. You see? Not all scars are ugly.