Dit artikel is ook verkrijgbaar in het Nederlands

Most people I meet have trouble getting my name right and I’m quite used to being called Pierce, Peter or Pierre. Admittedly they all mean the same thing, referring to the rock on which Christ decided to build His church (Matthew 16:18) — quite fitting for the son of a vicar, it would seem. If I’m in the mood, I may explain that it’s Pier, “as in Dun Laoghaire” or “as in jumping off the Pier”. Even in Holland, where I grew up, the name is unusual — and that’s because my name is not Dutch, but hails from Friesland, the most northern province of the Netherlands with its own distinct heritage, language, and of course — cattle.

My parents took the tradition of naming their children after their respective own parents very serious. My brother, being the oldest son of the oldest son, became the bearer of our paternal grandfather’s name — Harmannus or Mans for short — thereby continuing a sequence that’s lasted for generations. My sister was named Minke after my grandmother on my mother’s side, because tradition has it that the oldest daughter is named after her mother’s mother. When I arrived on the scene, I would have been called Lammechien after my father’s wonderful mother; only I’m of the male variety and so became the proud namesake of Pier, my maternal grandfather.

Pier Haagsma was happy and honoured to have his grandson named after him — his wife Minke Bosma was slightly disappointed that I “would never be a Haagsma”. Like the Kuipers family, there had been a generations old tradition of the oldest son inheriting his grandfather’s name — Jacob begot Pier, Pier begot Jacob and so on, until Jacob begot Ids, who was named after my uncle (as the second son, uncle Ids had been named after his maternal grandfather) who was executed by the Germans in 1944. If it wasn’t for that tragic event, the name Pier would not have been an option to my parents — like I said, they were serious about naming and didn’t believe in using a name that had already been claimed by another family member. In the Friesian tradition, me and my brother and sister as well as most of our Friesian cousins do not have a middle name — my American cousin Esther Minke being one of the few exceptions. With her middle name, Esther is of course named after — or for, as the Americans would say — the same grandmother.

My grandmother’s disappointment with me not carrying the Haagsma family name may well have been shared by one of her husband’s ancestors. It turns out that the name Pier arrives in the Haagsma family in 1811 — before the Haagsma name had even been officially adopted — when Jan Jakobs marries Ybeltje Piers. Note that the letter S after the second name denotes “son or daughter of”. Jan and Ybeltje name their first born son Jakob after his father, as was the norm. When their second son is born in 1817, he is of course named after Ybeltje’s father and so becomes Pier Jans — and since Jan has adopted the family name of Haagsma in 1815 in accordance with the new Napoleonic law, Pier Jans Haagsma is the first person in the lineage that was broken when my cousin became Ids Haagsma and I became Pier Kuipers.

As children we were always very much aware of our family history, especially on my mother’s side. Photographs of relatives long deceased adorned every corner of our home in Rotterdam, which — although rented — was in itself a family heirloom, occupied by members of the Haagsma clan since 1936 until my mother moved back to Friesland in 2002.

The portraits of Rinske Gietema and Jitske van Ketel, both dressed in traditional Friesian garb, were hung in the stairwell. They were my mother’s paternal and maternal grandmothers respectively, my mother carrying on the name Rinske. Following the rules of the naming traditions, that would mean that my mother is a second daughter, since the name of the maternal grandmother — Jitske — was reserved for the oldest daughter. This was indeed the case, but my aunt Jitske de Lange-Haagsma and her husband Piet both died from tubercolosis, in the same year that also witnessed the tragic death of Ids. They had been married for only a year.

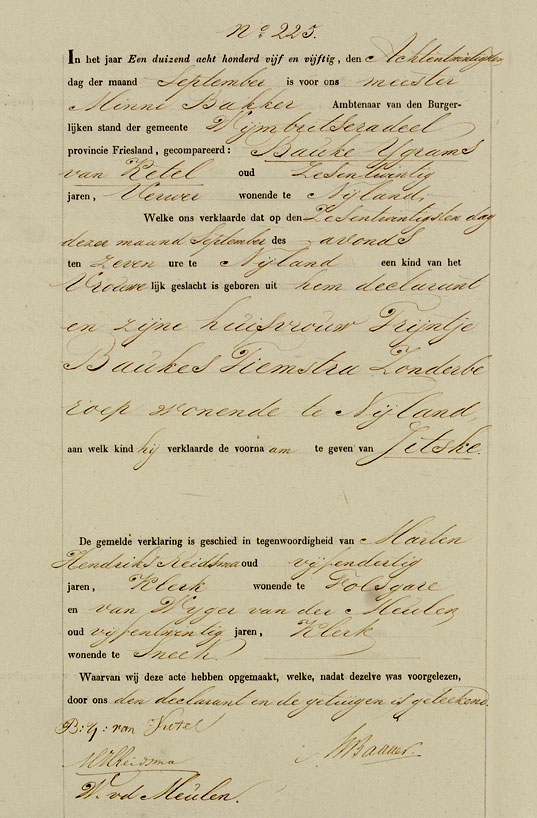

When I was visiting my mother a few months ago, we started talking about our family’s history once again. Among all the names, photographs and dates in my mother’s vast collection, the one thing she was missing was the precise birth date of Jitske van Ketel. Google came to the rescue and I soon found myself ploughing through dozens of genealogical websites, news groups and mailing lists. What we were looking for quickly came to light —the 26th September 1855, along with a copy of the entry in the relevant registry of births. What I had not expected however, was the avalanche of information that followed this discovery.

The birth certificate tells us that Jitske van Ketel was the oldest daughter of Bauke Ygrams van Ketel and Trijntje Baukes Tiemstra. Using our naming formula, we can deduce that Trijntje’s mother’s name must have been Jitske. What we can also assume, is that her oldest brother would have been called Ygram — if she had any brothers, that is. The plot thickens.

The pre-Christian tribes — including the Friesians — who occupied North-Western Europe before Irish monks came along to spread the Gospel, believed that their spirit would live on in descendants who bore their name. As a good pagan, you were obliged to name your children after your parents to ensure the survival of their souls. It appears that even in Christian times, the resulting tradition was pursued with a degree of fanaticism.

Although the names you’ve read about so far may seem unusual, Ygram is in fact very rare even in Friesland. Looking through the records of Jitske van Ketel’s siblings, I disovered that her dad went to extreme lengths in looking after the wellbeing of his father’s soul. Jitske did indeed have an older brother called Ygram, but he died in 1871 when he was just twenty and with no children of his own. Following Ygram’s death, no less than four more sons are born. All die when they are only a few months old — and all four were called Ygram.

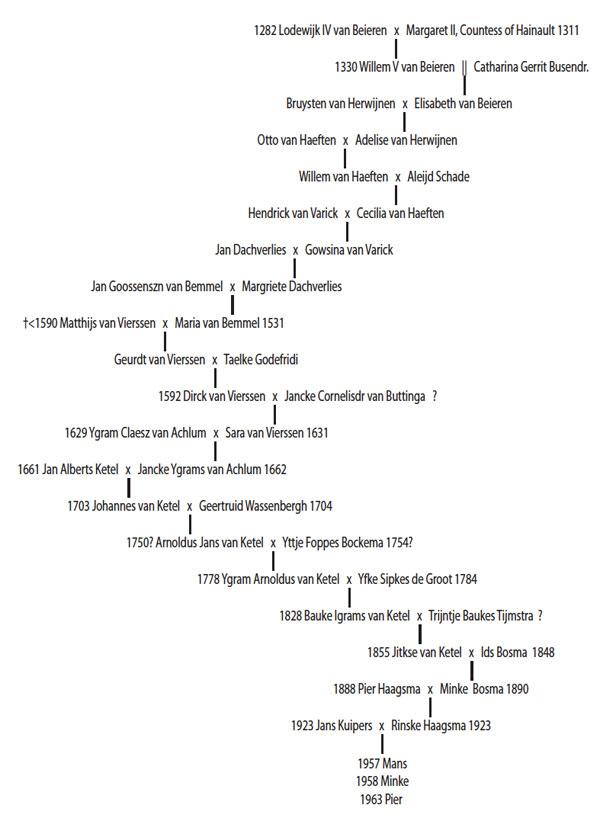

The available records of my ancestors the van Ketels go back much further than any other branch. Using the name Ygram as a marker, the trail first goes back as far as 1661, when Jancke Ygrams van Achlum introduces the name into the family by marrying Jan Alberts van Ketel. Jancke’s mother was a lady by the name of Sara van Vierssen, and this family has been traced back as far as the early 1500s — that’s 12 generations back from my own.

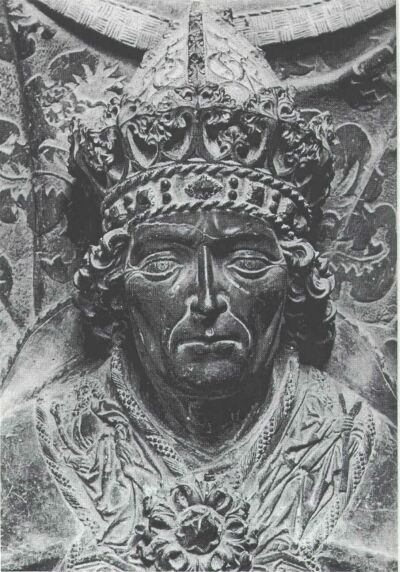

The pedigree does not stop there, however — far from it. Moving further and further back in time, we come across a girl by the name of Elisabeth who is born sometime in the mid 14th century. She is said to have been an illegitimate child of William V, Count of Holland and Zeeland, also known as William I, Duke of Bavaria. William was the son of no other than Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who lived and ruled in the first half of the 14th century.

I recently read Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose for a second time and with a slightly different perspective. When the Holy Roman Emperor is mentioned in the story, I now allow myself to think of this historic figure as my great18-grandfather. I wonder where I should go to claim my rightful place on the throne?

Oh, and in case you don’t believe me — check this out:

Credits

Ernst-Jan Munnik and his messages to the Yahoo newsgroup Friesland-Genealogy:

Message 19254

Message 19256

Alle Friezen, website that presents data from Frisian municipal archives

Genealogie Online

Tresoar, website of the Friesian Historic Museum

Google and Wikipedia

My mother’s archive